Is now the right moment for a flare gas sector in APAC?

By Chandran Jayabalan O&G Sector Manager, Asia, Aggreko

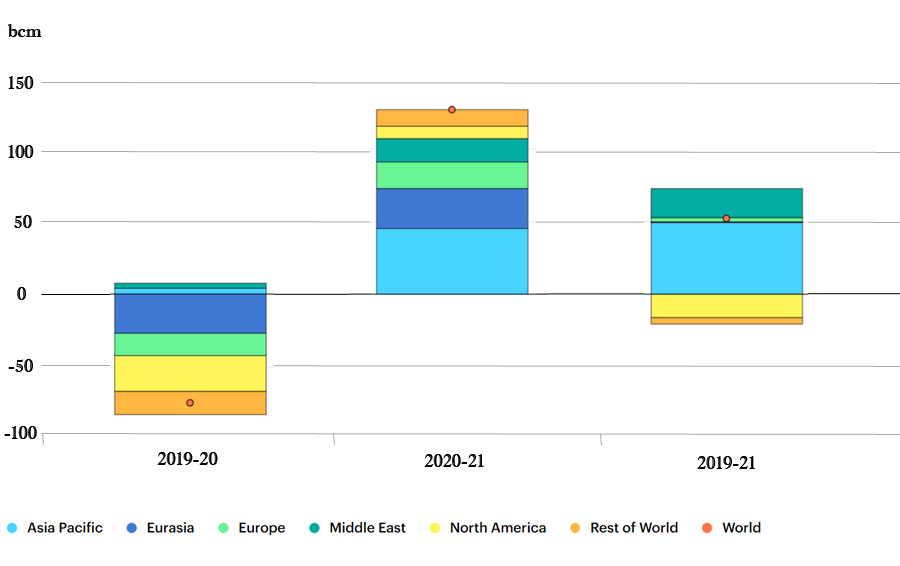

Rising gas demand and rising gas prices are raising eyebrows among the energy-intensive industries of the Asia Pacific. In 2020-2021, demand for natural gas grew more in this region than in any other, and in the depths of the pandemic the year before it was one of only two regions not to see demand fall.

That increased demand has been accompanied by rising prices, with JKM (Japan/Korea Marker) spot prices hitting US$56.326 per mmBtu in mid-October on the back of sustained high LNG demand from China. Prices may well fall, but factors such as production outages, high shipping costs and a Singaporean gas shortage suggest they may not fall far anytime soon.

These factors conspire to create a difficult situation for energy-intensive Asian businesses that are reliant on natural gas, who will be looking for solutions. Though no one such solution to explore is the regional potential of using flare gas – or associated petroleum gas (APG) – to power projects, or alternatively after cleaning and compressing or liquifying it transport it for use elsewhere via virtual pipelines.

In fact, a union of economic circumstance and technological maturity, means that this may well be the perfect moment for flare gas to power projects to make their mark in APAC.

Flare gas: the APAC opportunity

Flare gas – or associated gas – is most commonly the natural gas produced as a by-product of oil production. It is still routinely burned off for safety and production reasons. Ideally, this gas would be captured, processed and sold on, but the economics of doing so often make this impossible.

To illustrate by contrast, it is a relatively simple thing to capture and distribute flare gas somewhere like the United States, where there is a dense network of gathering pipelines connecting major drill sites. However, if you take an oil production site in an APAC archipelago nation, the logistics (and costs) of doing so are far less straightforward. Instead, the gas is burned, as the alternatives would be to either cease production or release the gas unburned, to harmful environmental effect.

There are two related problems here: one of cost-effectively capturing and processing the gas to make it usable, and one of then finding a profitable use for the gas. Fortunately, technology has advanced sufficiently to provide solutions to both: companies like Aggreko have designed modular, scalable solutions for capturing and processing that can be transported and commissioned easily in even remote sites. By designing a modular, containerised solution, logistic and operational costs can be minimised.

As for the second problem, there are broadly speaking two categories of solution. One is to use the captured gas on site or for co-located industrial processes, using it to power operations and displacing another liquid fuel, often diesel. This would create significant savings on fuel costs, as well as emissions. This is an ideal option for our remote archipelago example, which may not be grid-connected and grapple with high costs for buying in carbon intensive liquid fuels.

The other is to find a way to market, and when traditional gathering pipelines are unfeasible, this calls for a more innovative alternative, such as the virtual pipeline. The virtual pipeline sees the captured and converted gas distributed as CNG or LNG via some unconventional means, such as by road using specially designed truck fleets. Like the capture and processing stage, success for this model depends on flexible, modular equipment deployed at site, but once again the technology is now there to make that possible. A solution like this may be particularly attractive for markets like India, where stranded gas wells are spread over large distances, preventing economic extraction for lack of pipeline connectivity. Manoj Jain, the Chairman of GAIL India has already highlighted how the country’s plans to switch to LNG are under strain from higher prices; could this be the solution?

The flare gas volumes are certainly there to make an impact: 2020 saw India flare 1,493 million m³ of natural gas. Malaysia, Indonesia and Australia also flared 2,408 million m³, 1,883 million m³, and 977 million m³ respectively. Do these numbers suggest flare gas can single-handedly alleviate the region’s supply issues? No – but they do suggest that there are effective ways for oil and gas producers to create a new source of revenue in the region, and for gas-hungry industrials to find an additional source of fuel and take the sting out of the current high prices’ tail.

Beyond the economics

There are then additional reasons for APAC companies – on the supply and demand side – to consider flare gas to power and virtual pipeline options.

One is environmental: flaring is an environmentally ruinous practice, burning gas and producing CO2 for no productive purpose. For every Kwh that could have been produced by that gas, something else will have to do the job instead. Possibly diesel, possibly coal. At a time where all countries are under the climate change spotlight at COP 26, there is no escaping the need for greener ways of powering economies worldwide. Even in places where environmental concerns are secondary to economic development, large companies at the top of global supply chains are increasingly looking for greener practices throughout their supply chains, thanks to pressure from consumers, shareholders and governments alike. Using flare gas for power generation is not zero-carbon, but it does lower emissions substantially, particularly when it displaces more carbon-intensive fuels.

Relatedly, the regulatory risks to routine flaring are mounting. There has so far been little momentum in APAC for regulations specifically targeted at curtailing flaring, as there have been in various Western economies. However, there is a growing risk from indirect regulations such as carbon taxes. Singapore already has one, Thailand has a framework in place, Malaysia has been talking about it – momentum is building in this respect. Reducing flaring – and displacing other fossil fuels – could be a vital tool in reducing liability when these laws arrive.

Timing is everything

It seems then, that the timing may well be opportune for an APAC flare gas sector – incorporating both flare gas to power and virtual pipelines – to emerge and make a mark. The brute economics of high gas prices are a major part of the equation, but environmental and regulatory concerns (and their economic ramifications) also add weight to the case. At the same time, technology has never been better able to deliver precisely these types of projects as flexibly and cost-effectively as it can now. Timing is everything – and this may well be the moment for flare gas in APAC.